Tokyo Story Film Review – Yasujiro Ozu’s 1953 Masterpiece About The Bonds Of Family And The Unacknowledged Importance Of Bucket Hats

Film Rating

Foreigners one day will understand my films.

Yasujirō Ozu

Tokyo Story‘s history is well known at this point, with it originally seen as “Too Japanese” to be exported out to American audiences after its initial release in 1953. It wasn’t until a 1972 screening in New York where it started to gain status and recognition. It climbed the ranks of critics top films and eventually landed as one of the top films in Sight and Sounds top movies of all-time list.

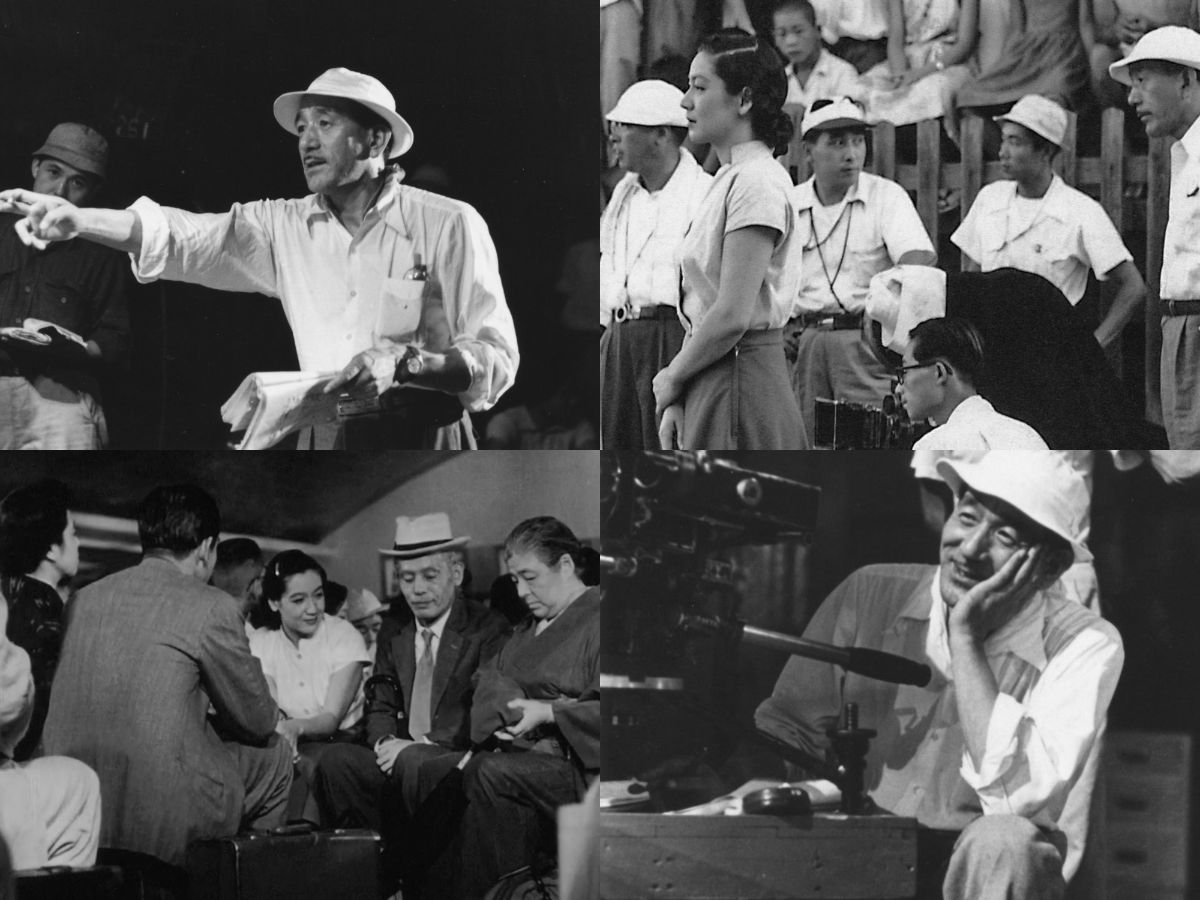

Unfortunately for western audiences in the ’50s and ’60s, they weren’t able to experience Ozu’s masterpiece when they could have used it the most. Although loosely based on the 1937 American film Make Way for Tomorrow, Tokyo Story showcased its own Japanese specific themes about post-war Japan and the loss of traditional Japanese family. Hidden under those themes though is a much less talked about message, one that I’ve never seen articulated in print (I’m not saying it doesn’t exist, I was just not able to find it myself when researching). That is, naturally, Ozu’s unmentioned love and quiet promotion of bucket hats.

The bucket hat that we know today has gone through many iterations over the years. Although popularized in the west in the ’60s and again with a resurgence in the late 90s, bucket hats in their cloth form have been around since the early 1900s first used by fishermen. However, the bucket hat itself is pretty much just a modern version of the Japanese Kasa hats which have been around much longer. Bucket hats, and the Kasa hats before them, are both functional, giving shade to a full 360 degrees, as well as helping to show status among their users depending on the specific style and decoration.

So, what do bucket hats and one of the most influential Japanese directors of all time have in common? Well, I know it may sound ridiculous to some, and it was never directly vocalized by Ozu himself, but themes about hats, and specifically bucket hats, run constantly through his films. For example, most of Ozu’s films revolve around couples trying to marry off a daughter.

The daughters in Ozu’s films are like the bucket hat, not always perfect to others, but always perfectly and uniquely themselves. Characters in those films, parents and third parties, are like manufacturers or brands that, although they may have good intentions, are trying to push two people or things together that may not fit. It is always better for the daughter (or hat), to help in finding their perfect counterpart themselves. To do it without their consent is likely to lead to drama, which although great entertainment for movie watchers, is not good for the characters themselves.

Tokyo Story is different than Ozu’s other films with its allegory. Instead of having the daughters be the stand-in for bucket hats he makes the bold decision to instead have the older couple stand-in for the hats.

When we first see Shūkichi and Tomi, the elder Hirayamas, in their home town of Onomichi, a small fishing and port town, they are sitting happy as they talk about their upcoming journey to Tokyo to visit their grown children. Ozu, never one for flashy camera movements, keeps the shot low and stationary, allowing us to sit along with the couple wondering what might await them and us in Tokyo.

The next shot is of the train leaving Onomichi, beginning its long 800 km journey. Ozu doesn’t show the journey, instead allowing most of the action and scenes to happen offscreen. It’s similar to how we don’t know the exact path that bucket hats took from fishermen on the outskirts of society to the greater public. But, like the Hirayamas traveling from their small fishing village to the big city, they eventually make it.

Upon making it to Tokyo, the elder couple is almost immediately viewed as an inconvenience by their children, all of whom have their own lives they are living with no time for their parents. All of this is shown to the viewer with more of Ozu’s typical filming style, like a bucket hat, there are little to no cuts.

The one character that does seem to genuinely enjoy spending time with the couple is Noriko, the widowed wife of their son Shōji, who died in the war several years earlier. Noriko is like an open and receptive purchaser of a bucket hat. She sees it/them not as an out of date burden, but instead as something that can bring her closer to something she once had and lost. They are not old and unhip, but instead caring and helpful. Their relationship isn’t one-sided either, she spends time and money on the couple, happily showing them around the city. Similar to a person with a new beautiful item of clothing they want to show off.

Eventually, the parents decide to call their trip early and go back home. They sit in the train station seeming a bit more dejected than when they first arrived, despite Noriko’s attentiveness. When they first came, they were both wide-brimmed and excited, but now having seen the city and their children who have little time for them, part of that 360-degree protection they came with is gone. That is why we see only Shūkichi with a bucket-like hat on, where his other half, Tomi, has no covering at all, having had it metaphorically stripped during the trip.

Tomi faints on the return journey and then shortly after falls ill. The family comes to her bedside, but she soon dies. The children of the family mourn, but also quickly leave home again, with only Noriko staying behind an extra day to share in a temporary moment of happiness with the father as they watch a sunset together.

Life moves on. Trends move on. Very few connections stay with us for our entire lives. Some people you think are the closest move on and become distant while others become closer. There are clothing items that may seem like they aren’t your thing or out of date or not your style, that once you give them a chance will stay with you forever.

Uzo’s knew this about bucket hats, something that he clearly made a connection with during his life, but he must have known hat the greater public did not think of them in the same way as he did. By showing the bucket hats as people, as parents, as some of the ones we think of as closest to ourselves, and showing what happens to them when they are rejected, he was hoping to show the world of just how important and great the hats are.

It’s because of this fact that I find it so sad that the film wasn’t shown to western audiences and widely distributed until the mid-70s. By that point in western culture, bucket hats were already seen as something of a joke being associated more with the bumbling dope Gilligan from Gilligan’s Island instead of one of the world’s greats directors.

There was a time in the ’90s when it seemed like Ozu’s bucket hats might make a return to prominence as they were worn by rappers and fashion icons. If only with every purchase of a bucket hat there was also a VHS copy of Tokyo Story, people wouldn’t have thought of the hats as a disposable fad, as they inevitably did, but instead of something to be cherished and loved.

Hopefully now, with Tokyo Story’s influence greater than it ever has been before, the next time bucket hats become big, the world knows better and treats them with the love and respect they deserve.

These are the useless things that make life pleasant.

Yasujirō Ozu

Film Rating

Find The Film

Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tokyo_Story

- http://explore.bfi.org.uk/sightandsoundpolls/2012/critics/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yasujir%C5%8D_Ozu

- https://www.crfashionbook.com/fashion/a21967443/history-of-bucket-hat-fashion/

- http://yabai.com/p/3335

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bucket_hat

- https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/301-tokyo-story-compassionate-detachment